05 Apr, 2014

by Haakon Haagensen

Excerpt from AMAZONAS Magazine, May/June 2014

There is no armored catfish more popular among aquarists than the black and whiteHypancistrus from the Rio Xingu in Brazil known as the Zebra Pleco. Many pleco forms are near extinction in their natural habitat; we have the unique opportunity to conserve them in the aquarium, at least on a small scale.

Would-be breeders please take note: People are willing to pay big money for these catfish.

Ever since the late 1980s, when the first pictures of a black and white striped Peckoltia (L46) were published, aquarists all over the world have enjoyed keeping and breeding these little gems in their home aquariums. It did not take long for new and slightly different forms of black and white striped plecos to be discovered and shipped out of Brazil. Although aquarium magazines everywhere provided tantalizing images of the early exports, most of those fancy and shockingly expensive plecos went to wealthy customers in Asia.

In the heyday of the L-numbers, importers clamored to present the latest sensational and exclusive catfish species. The fewer specimens were available, the higher the prices. Both L236 and L250 were supposedly caught in very difficult-to-reach areas in an Indian reservation on the Rio Iriri, a Rio Xingu tributary upstream of Altamira, but later it became clear that L236 is also found in the Rio Xingu, even in the same region as the well-known L333. (Specifying false catch sites is a practice commonly employed to prevent other collectors from visiting the true locales.) There is still controversy as to whether there are any Hypancistrus in the Rio Iriri; experienced collectors and travelers claim that there are none, but others maintain that no one has searched hard enough to find them.

In recent years, new restrictions by the IBAMA (Brazil’s conservation authority, similar to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service) have made it harder to find these fishes in the trade. Fortunately, most have already been propagated in the aquarium. Although this has partially satisfied the demands for these fishes, it has also led to a new and complicated issue: hybridization. It turns out that it is anything but easy to distinguish the different but very similar forms from one another, even those found in the same river system.

Species confusion

Given the impending completion of the Belo Monte Dam Complex near Altamira on the lower Xingu, we should all try to learn as much as we can about these great catfishes before they disappear from their natural habitats. About 15 forms of Hypancistrus are known from the lower part of the Xingu River between Altamira and Porto do Moz. Some of them, such as L250, are still shrouded in mystery, but it is likely that they, too, come from this region. Besides the many L-number catfishes, there are others that are difficult to identify. It is unlikely that they are all separate species, since they all come from a single river and are closely related.

While it is not unusual to find several forms of a species in a single habitat, the huge number of forms that occur in the Rio Xingu is confusing. Entirely different standards are needed to categorize these fishes, and it is hardly surprising that some people are so overwhelmed by the sheer variety that they just put their heads in the sand.

There is a huge amount of general information about these catfishes out there. Breeding reports, husbandry experiences, and identification guides are ubiquitous on the Internet; some sources are reliable, others questionable. What is certain is that so far, nobody has a foolproof way to identify the many types and forms.

With all this in mind, I have tried to summarize the available information here. I admit that this article does not give any definitive answers, but I hope it leads to a better understanding of this amazing catfish group.

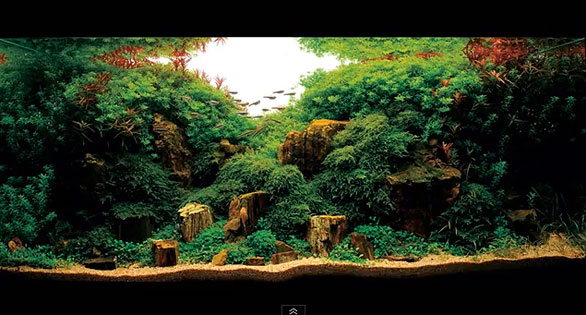

Clearwater habitat

The various forms of black and white striped Hypancistrus are usually caught between Altamira and Porto do Moz in water 6–100 feet (2–30 m) deep. They occur in moderate to fast-flowing, soft to slightly acidic warm water. They prefer rock structures and like to hide in cracks and crevices. The water parameters, which are constant almost all year, are: pH 6.0–6.5, very low conductivity, and temperatures of 82–90°F (28–32°C). The distribution of various populations is restricted by the extreme currents and precipitous waterfalls, so they stay in their own territories.

However, one must not underestimate the vastness of the region: the Xingu River basin is larger than most people can imagine. The river is several miles wide in places and contains some islands. Large rocks that create rapids alternate with extensive sandy areas, representing distribution barriers for these littoral-colonizing catfishes.

The best-known Hypancistrus forms of the Rio Xingu

A form that occurs without the presence of another from the same genus is usually referred as a valid or emerging species. It seems that there are four of these base forms in the Rio Xingu:Hypancistrus zebra, L174, L66, and L333. The latter two are larger than the rest (6–6.4 inches/15–16 cm TL). Hopefully, detailed molecular DNA studies will soon reveal more about their genetic relationships, but there is no doubt that the forms are all closely related. A very comprehensive study is currently in progress and should shed some light on the issue.

The four main forms or species

Hypancistrus zebra is remarkably uniform and is very attractively patterned. Occasionally, H. zebra specimens with pattern variations, such as L98, do occur. Through breeding experiments, we know that this variation is not heritable. L250 may also be a H. zebra variant; all known images show specimens with silvery eyes, a feature known only from H. zebra. The blue shimmer in the fins of H. zebra is also present. However, most Hypancistrus from the Rio Xingu have brown to reddish eyes and do not show any trace of blue on the fins. Without further imports, a clarification in this case is difficult. The distribution of H. zebra includes four to six different localities between Altamira and Belo Monte. H. zebra is usually found in deep water. Based on aquarium observations, the species is more active at night. Both factors suggest that the zebra pattern is well suited for low light conditions.

Hypancistrus sp. L66 is a large and robust form with a black wormline pattern on a gray or yellowish background. While L333 is usually cream-colored, L66 is more commonly white and gray. In mature animals, the pattern is denser and finer, often breaking down into stripes or even spots. However, color and pattern are not reliable differentiation features between the two. Compared to L333, L66 is flatter and the caudal fin is more deeply forked. L66 is one of the most widespread forms in the river; it occurs from Altamira down to the huge lake located at the river’s end. This form is also found in the tributaries.

Hypancistrus sp. L174 is easy to recognize: the most characteristic feature of this deep-water species is its small eyes. There are only a few known locations, which are downstream of Altamira. L174 is, so far, the smallest known member of the genus with a maximum length of 3.2 inches (8 cm). The pattern always consists of dark dots or spots, which led to the nickname “Ocelot Pleco.” Contrary to previous reports, L174 shares no habitats with H. zebra.

Hypancistrus sp. L333 has a high-backed, compact, sturdy shape with a reverse D-shaped caudal fin. The many known variants differ in both pattern and color. Usually, the pattern of wormlines becomes narrower and shows less contrast with age. Some individuals have beautiful wide lines. This rather large species is mostly caught near Porto do Moz, but is also found near Vitoria do Xingu.

The Rest

The biggest challenge for aquarists is to identify the many other forms that occur in the river, as they are all very similar. They have a bright base color, which can vary from pale yellow to gray and white. The pattern consists of dark wormlines or spots. The eyes are brown and their size varies. Some forms have a short, compact build, while others are rather slim. The caudal fin can have long filaments or be small and non-elongated. The head shape is not uniform; it can be pointed or rounded. Most hobbyists pay way too much attention to the color pattern. This is where there is the most overlap between the various forms, which makes identification impossible. Never rely on the color pattern to identify these forms!

Hypancistrus sp. “Mimic” lives syntopic with L174 near Altamira. In the last few years, it was often mistaken in the trade for L399/L400 or L173. Hypancistrus sp. L174, L399, L400, and “Mimic” share one feature: the dark spot pattern. Hypancistrus sp. L174 and “Mimic” have much smaller eyes than the others. Hypancistrus sp. “Mimic” is larger and has a flatter body and a more pointed head than L174. Young animals are almost impossible to distinguish. Hypancistrus sp. “Mimic” babies have a striped pattern, similar to H. zebra, whereas young L174 always have a spotted pattern.

Hypancistrus sp. “Lower Xingu” is a complex group of similar forms that are very difficult to distinguish. Apparently, this group is in the process of slowly separating into individual new species. They live within a radius of just over 6 miles (10 km) of Belo Monte. Janne Ekström works there every day with these catfishes and says the following: “There are four or five variants in this complex. One of them, known as H. sp. ‘Gurupa,’ is always light gray to white and has smaller eyes relative to the head size. The body shape is compact and the caudal fin has no filaments or extensions. A second variant is black and white, with a flatter body and extended caudal. This variant is very similar to L173; some look exactly like it (not all L173 look like discolored H. zebra). The third variant is also black and white, but shares the compact body and the lack of filaments with H. sp. ‘Gurupa.’ It resembles L333, but has a pattern that varies from spots to broad, irregularly arranged stripes. L399 and L400 are from the same region and possibly also belong to this group.”

Hypancistrus sp. L287/L399/L400: These are three numbers for one and the same form, in my opinion. It is apparently a highly variable form. Although spotting is the most common pattern, there are specimens that have very broad lines or fine lines with plenty of open space. Intense captive breeding has revealed an enormous number of variations. Characteristics of coveted forms such as L173, L236, and L345 are among them. These L-numbers may be all morphs of the same form. L399 differs from L400 only slightly by a somewhat more delicate physique—L400 appears more robust.

This group consists of smaller catfishes (about 4.8 inches/12 cm) that are more elongated and a little less bulky. They have large, forked caudal fins with the longest filaments in the genus. There are variations in the anatomy. Such immense variability among loricariids is not common and is very noticeable in this case. To complicate matters, the home of these catfishes is in the surroundings of Belo Monte.

During just one dive, different variants can be caught in a single locality. They share their habitat with some of the main species in the river (L66, L333, and H. zebra). Belo Monte seems to be a hotspot for the development of new forms and species. So far, the gene flow between these forms has not been well studied, but a form like L173 suggests that there are regular natural hybridizations among some of them. The question is, to what extent is this happening?

Hypancistrus sp. L173 is a highly sought-after but controversial form from near Belo Monte. The similarity to H. zebra is striking, especially in juveniles. However, there are differences: L173 has brown eyes, a rather off-white base color, a variable wormline pattern, a taller and more compact body, and a longer caudal fin. This form also grows larger than H. zebra. In the hobby, L173 was unfortunately hybridized with H. zebra to produce more of the “L173 type.” Some L173 lines differ so much from the norm that it is hard to believe that they belong to this form. Not all individuals have the typical pattern. Some offspring of L400 show a pattern similar to L173, hence, a close genetic relationship is very likely. It is important to note that L173 is not a morph of H. zebra, as was previously assumed.

The commercially available L173b should be regarded with skepticism. (The “b” was introduced by Aquarium Glaser. Specimens that differ externally from the normal habitus were identified with the letter “b.” Individuals with a typical pattern and color would therefore be “L173a.”)

Hypancistrus sp. L236: The image from the initial introduction of L236 shows a fish with a few wide black wormlines on a pale cream background—an unusual pattern, even within this genus. Nevertheless, such individuals occur in all forms with wormlines, although it is rare. The individual shown shared many characteristics with L66, such as the flat, slender physique and the forked caudal fin. However, there are also examples known that combine the physique of L333 with the pattern of L236. These are L333, which are advertised as L236 because of their pattern. Over time, L236 has become a “brand.” Each Hypancistrus that corresponded to the original pattern, no matter where it came from or what body shape it had, was called L236.

Many catfish friends seem to forget or ignore the fact that all the wormline Hypancistrus are inconsistent in their patterns. Two parents with exactly matching patterns will not guarantee that the same pattern will show up in the offspring. With the exception of H. zebra, there is noHypancistrus form with a consistent pattern that is found in large quantities. Even in Colombian species such as H. debilittera and L340, there are animals with a “negative pattern” (H. sp. “Platinum”). However, this is never the standard pattern of any species.

Starting with an “ideal pair,” we attempted to select out the dark parts of the body pattern. At the beginning, 10 percent of the offspring corresponded to the desired appearance. After 10 years, the yield of fishes with the desired pattern increased to 30 percent per clutch. This shows that a certain color or pattern type can be bred selectively in the aquarium. In addition, it should be noted that at the juvenile stage (1.6–2.4 inches/4–6 cm), all Xingu forms except H. zebra look very similar, so they cannot be identified by the pattern. Therefore, it is important to see the parents in order to assess whether a breeder has properly named the animals or not. The impressive pattern of babies usually becomes denser and darker with age.

Thoughts on the development

Thoughts on the development

of Hypancistrus in the Rio Xingu

Currently, the Rio Xingu is the most species-rich habitat for loricariids. Among them are many forms and species that are still evolving—and not only Hypancistrus. Spectracanthicus, Scobinancistrus (at least six), Ancistrus, Baryancistrus (at least nine), and others are represented by many similar forms that differ by color pattern. This shows that this river, with its natural boundaries, contributes to the rise of new species. This may be the case for Hypancistrus, although they differ much more, not just in the pattern. The large variation is the result of specific adaptations to the environment, such as predation, food, the structure of the riverbed, water depth, flow, and intraspecific communication.

The rapids, waterfalls, and sandbars form natural barriers in the river, so it is not surprising that one finds isolated populations. This physical isolation, and the fact that the catfishes do not move very much and thus rarely overcome these boundaries, allow these populations to evolve into new, slightly different forms as they adapt to the habitat.

It seems that some forms exist very close to each other, even in the same biotope. How they differentiate to find their partners, and whether this is done by looks, smells, sounds, or ecological niches, such as water depth or rock structures, is one of many questions that remain. For example, it is not yet known whether all Hypancistrus can interbreed. Right now it looks like that is the case. The possibility that all forms hybridize is certainly greater in the aquarium than it is in nature. We do not yet know how mixing takes place in the natural habitat or what makes a fish choose a given partner.

Maintaining pure aquarium strains

Tropical fishes occurring in different morphs is nothing new, and these forms can serve as a basis for breeding new lines. One of the best-known examples is the discus (Symphysodon sp.). In this genus, even cross-species hybrids are widely accepted. However, catfish enthusiasts tend to reject that idea, and the results of hybridizations from Eastern Europe are frowned upon by serious hobbyists. In Asia, however, the creation of new lines seems to have been widely accepted. I personally hope that this view will not prevail elsewhere.

Hypancistrus belongs to the undemanding L-catfishes, and this makes the genus popular with beginners, which in turn increases the risk of unintentional hybridizations. It is well described that the various forms cross and produce fertile offspring (a list of known hybrids can be found atwww.L-Welse.com). Take, for example, the hybrid offspring of L66 and L333. Such fry are simply given a number and then passed on, knowingly or not. Thus, we run the risk of creating singular hybrid strains with unknown provenance. This happened long ago with the “Common Bristlenose Pleco” (Ancistrus sp.).

It is important to know the origin of your animals. Are they wild caught, captive-bred from a breeder, or bought as individual animals? There are countless discussions on the Internet about the identity of individual animals. Many Hypancistrus from the Rio Xingu are expensive, and most fish keepers who care for them try to keep them pure, but some people do not want to know what they have in their aquariums if the truth does not agree with their wishful thinking.

Due to IBAMA restrictions in Brazil, for a long time there were no wild-caught animals available commercially. Even today, most fishes offered are tank-raised offspring. Consequently, it is all the more important for breeders to be aware of the identity of their catfishes and not simply pass them on under a name that will bring the greatest profit. While H. zebra is propagated in large numbers worldwide, some species and forms are very rarely kept. These are the species and forms we must multiply and preserve!

The Rio Xingu offers a unique display of evolution, where we can observe the formation of species within a lifetime. If we have an interest in exploring this unique group of fishes, we must act quickly. Time is running out: we all know about the Belo Monte Complex, now under construction. In a few years, the environment could be so severely degraded that many fishes might disappear. The reality is that we are destroying a treasure before we have understood it. However, we do have a breeding foundation for maintaining some black and white Hypancistrus, at least in the aquarium, for a long time to come.

Acknowledgments: This article is the result of years of personal experience and research. Still, I would not be able to present this work without the help of many knowledgeable people in the catfish world. I am grateful for their time, their dedication, their criticism, and their willingness to communicate. I am sure we will all continue to benefit from the great collaboration we have established. My thanks go to my friends Erlend D. Bertelsen, Hans Johan Mengshoel, and Bjørn Iversen (all from Norway), Janne Ekström (Sweden/Brazil), Mikael Håkansson (Sweden), Heriberto Gimênes, Jr. (Brazil), Saul Paredes, Nathan Lujan, Jon Armbruster, and Milton Tan (all from U.S.), Daniel Konn-Vetterlein, Ingo Seidel, Torsten Schwede, and Hans-Georg Evers (all from Germany).

References

Budrovcan, R. 2011. Die L236 Story—Teil 2. BSSW-Report 23 (3): 9–17.

Ekström, J. 2010. Der Belo-Monte-Staudamm am Rio Xingu—ein vorprogrammiertes Desaster. AMAZONAS 31: 8–12.

Evers, H.-G. 2005. Quo vadis, Hypancistrus zebra? AMAZONAS 2 (German): 36–8.

Evers, H.-G. and I. Seidel. 2002. Wels-Atlas, Band 1, Mergus Verlag, Melle, Germany.

Lechner, W., M. Geiger, and A. Werner. 2005. Neues aus der Gattung Hypancistrus—Teil 1. DATZ 58 (11): 6–13.

———. 2005. Neues aus der Gattung Hypancistrus—Teil 2. DATZ 58 (12): 10–17.

Schmidt, E. 2011. Die L236 Story—Teil 3. BSSW-Report 23 (2): 18–21.

Schraml, E. and F. Schäfer. 2004. Aqualog Loricariidae All L-Numbers. Aqualog Verlag A.C.S., Rodgau, Germany.

Seidel, I. 2005a. Besonderes zur Gattung Hypancistrus. AMAZONAS 2 (German): 16–25.

———. 2005b. Die Neuesten Hypancistrus-Arten. AMAZONAS 2 (German): 26–9.

———. 2007. Schon wieder ein neuer Hypancistrus aus dem Unterlauf des Rio Xingu. Aquar Fachmag 193: 30–31.

———. 2008. Back to Nature: Guide to L-Catfishes (Loricariidae). Fohrman Aquaristik AB, Jonsered, Sweden.

———. 2010. Hypancistrus-Fibel—Die schönsten L-Welse im Aquarium. Dähne-Verlag, Ettlingen, Germany.

———. 2011a. Der Rio Xingu in Brasilien—ein Paradies in großer Gefahr. Aquar Fachmag 213: 4–7.

———. 2011b. Rio Xingu—große Artenvielfalt durch verschiedene Lebensräume. Aquar Fachmag 213: 8–19.

———. 2011c. Die vom Aussterben bedrohten L-Welse vom Rio Xingu. Aquar Fachmag 213: 20–27.

———. 2011d. Die L236 Story—Teil 1. BSSW-Report 23 (3): 6–8.

Seidel, I. and H.-G. Evers. 2005. Wels-Atlas, Band 2. Mergus Verlag, Melle, Germany.

Stawikowski, R., I. Seidel, and A. Werner. 2004. DATZ Spezial: L-Numbers. Verlag Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart, Germany.

Trusch, S. 2005. Bereits gezüchtet: Hypancistrus sp. “Belo Monte.” AMAZONAS 2: 30–35.