Can unusual suspects reform the aquarium livestock trade?

09 May, 2013

CORAL Senior Editor Ret Talbot, lead author of THE BANGGAI CARDINALFISH, coming soon from the Banggai Rescue Project.

Opinion

By Ret Talbot

Excerpt from CORAL, May/June 2013

I was having a conversation last night with a person who knows his way around the marine aquarium livestock trade and hobby. We were discussing the future of both trade and hobby in light of the increasing number of potential restrictions to keeping fishes and other marine animals. Any of these—the current NOAA proposal to list 66 species of coral under the Endangered Species Act or the Invasive Fish and Wildlife Prevention Act, recently reintroduced in the U.S. Congress, for example—could end the aquarium trade as we know it.

So could recent, well-funded efforts by, amongst others, the Environmental Defense Fund and the Defenders of Wildlife. I suppose the stunned outrage and anger with which some aquarists have responded to these threats—real and perceived—on social media and in online forums is understandable, but should we really be stunned or outraged?

Collection live aquarium fishes with cyanide, a practice still rampant in the Philippines and Indonesia, according to many observers. Image by Lynn Funkhauser, from The Conscientious Marine Aquarist.

While there are plenty of solid arguments against many of the anti-trade initiatives that seem to keep popping up like Xenia in a reef tank, the fact of the matter is that aquarists may well be better served by focusing our efforts inward on the aquarium livestock trade itself.

Stunned or dead or dying reef fishes after exposure to cyanide. Image by Lynn Funkhauser, from The Conscientious Marine Aquarist.

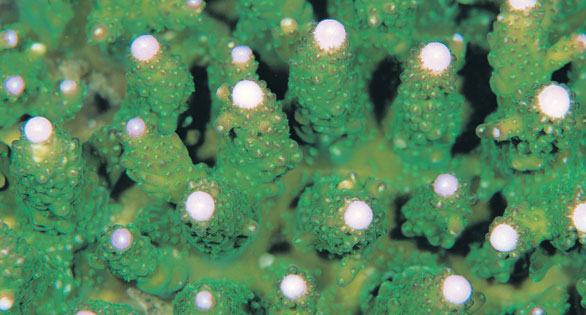

After all, the trade has made itself a viable target for anti-trade activists. Let us not forget recent import data shows the aquarium trade still depends primarily on countries where destructive and illegal fishing techniques are the norm rather than the exception (think cyanide use in Indonesia and the Philippines). Let us not forget that smuggling of species remains commonplace (think illegal wild Banggai Cardinalfish exported from Indonesia or Clipperton Angelfish coming into California). Let us not forget that carelessness and ignorance have led to invasive species introductions that have had significant ecosystem impacts (think Volitans Lionfish in the Caribbean and Caulerpa introductions in Europe and the U.S.).

Many important voices have advocated for trade reform over the past two decades, and many positive steps have been taken in the right direction. Nonetheless, none of these efforts have resulted in the type of systemic change required to remove—or at least reduce in size—the bullseye from the back of the aquarium trade. Why is this? Does the trade lack the will? The resources? The imagination? The incentive? Whatever the reason, as my colleague with whom I was having this conversation pointed out, “The same approaches from the same people haven’t worked in 20 years.”

Maybe it’s time to look to some unusual suspects as the drivers of change.

Game Changers?

An important paper was published about a year ago in the journal Zoo Biology that suggests a new group of players may be the ones to effect real change in the aquarium trade. Titled “Opportunities for Public Aquariums to Increase the Sustainability of the Aquatic Animal Trade” (Tlusty et al., 2012), the paper contains an intrinsic premise: the aquatic animal trade is currently deficient when it comes to sustainability.

More important, however, the paper points out that it doesn’t have to be, and public aquariums have an opportunity to play an important leadership role in transforming the trade from a threat to a positive force for aquatic conservation. While there are other entities that also have the opportunity to play a significant role in reforming trade, I’d like to take a moment here to explore the potential role of public aquariums.

Aquatic tunnel at the Georgia Aquarium, Atlanta: Can public aquariums, using some of the same sources that supply animals to the marine aquarium hobby, help lead the way toward a more sustainable livestock trade? Image: Sean Pavone Photo/Shutterstock.

Public aquariums have always had an uneasy relationship with the aquarium hobby. While many curators at public aquariums are home aquarists themselves—and although many of the researchers on staff will credit their passion for all things aquatic to keeping a fish tank as a kid—the overall institutional sentiment has too often been “it’s probably best if you leave it to the professionals.” After all, the aquarium hobby and the trade that supplies it with animals have been responsible for all manner of all-too-public mishaps and missteps that make the institutions—the professionals—want to distance themselves from the “hobbyists.” Gone, some say, are the glory days of late-nineteenth-century amateur scientists seriously engaged with professional scientists in the parlors and conservatories of Victorian homes.

As the Zoo Biology paper shows, public aquariums, however, cannot quite so easily distance themselves from home aquarists and the aquarium trade that supplies both with live animals. Public aquariums have a complex relationship with home aquarists and the livestock trade whether they want to acknowledge it or not. The reality is that aquarists visit public aquariums in significant numbers, and visitors to public aquariums are more likely to begin keeping fishes and other aquatic organisms at home than the general public. Put another way, the authors of the paper present data showing public aquariums make new home aquarists. In addition, public aquariums often rely on the same trade networks of collectors and importers as do home aquarists. While some public aquariums mount their own collecting expeditions, almost all rely to a greater or lesser extent on the same importers who supply the animals in our home aquariums.

The necessary conclusion of this analysis is that, if the aquarium trade is deficient when it comes to sustainability, then public aquariums are complicit in that deficiency. To be fair, this complicity is offset at the best public aquariums through messaging about conservation and educational initiatives, but the fundamental truth remains that as long as the aquarium trade exists, public aquariums, either directly or indirectly, will play a significant role in supporting that trade by creating new home aquarists, encouraging existing aquarists, and directly acquiring animals through established trade networks. It follows that public aquariums, given this overlap with the aquarium trade, should increasingly be incentivized to take an active role in effecting trade reform, and this should be very good news for the home aquarist.

Not Reinventing the Wheel

Public aquariums, unlike many of the people and organizations that have attempted trade reform over the past two decades, have resources and expertise giving them a very good chance of actually effecting positive systemic change. Unlike the “same approaches from the same people,” public aquariums are in a unique position to improve the sustainability ethos in the trade.

Take, for example, the role public aquariums have adopted when it comes to sustainable seafood (and let’s recall that the seafood trade didn’t make a move until that trade was threatened). In a little over a decade, some public aquariums (such as Monterey Bay Aquarium and New England Aquarium) have, in essence, become non-governmental environmental organizations that have played a leading role in promoting sustainable fisheries and environmental stewardship. They have provided invaluable technical knowledge to the seafood industry through their own research initiatives. They have launched educational initiatives within their institutions that have put the topic of sustainable seafood on the front page and above the fold, and they have taken that message to the general public through a bevy of outreach programs.

What if public aquariums did the same for the aquarium trade? As the Zoo Biology paper points out, “…given that public aquariums exist to exhibit aquatic organisms for educational purposes, it is ironic that fish species destined for the plate currently have more sustainability efforts directed at them than do live fishes kept by private aquarists and public aquariums.” Is it too much to argue that the seafood industry’s past could be the aquarium trade’s future?

There are many other strengths beyond public aquariums’ engagement in sustainable seafood that could easily be applied to promoting a sustainable marine aquarium trade. Public aquariums, for example, are already educational leaders and have become trusted sources for important conservation messaging on a whole host of environmental concerns from global climate change to conservation of habitat. Think of the ways public aquariums could leverage this educational strength toward developing and teaching best practices for the aquarium trade and informing the public about the risks and benefits associated with aquarium keeping. Through already established social pathways, public aquariums are in a unique position to help educate aquarists about sustainable options for purchasing fishes and other aquatic organisms, and they can be instrumental in creating market-based initiatives linking sustainable aquarium fisheries to retail outlets.

Despite government regulations, illegal poaching and uninspected exports of the Banggai Cardinalfish from Indonesia place severe pressures on a species listed as Endangered by the IUCN. Image by Matthew Wittenrich for the Banggai Rescue Project.

As respected leaders in sustainability and conservation, public aquariums can accomplish a lot simply by actively supporting sustainable (or, in some cases, withdrawing support from unsustainable) initiatives in the trade. Whether these are specific fisheries, trade routes, wholesalers, or retailers, the support of public aquariums can give credence and bring attention to those elements of the trade that are “doing it right.” Conversely, as trusted thought leaders, public aquariums can marginalize those elements of the trade that are not achieving or at least moving toward sustainability. Likewise, staff researchers at public aquariums are in a unique position to provide much-needed impartial oversight and data analysis of the trade, which may lead to important public-private partnerships including, but not limited to, serving in an advisory capacity to the trade and participating in multi-stakeholder processes toward developing best practices.

Of course there are many other areas in which public aquariums can engage the trade in an effort to promote sustainability. Perhaps the most public of these has been the role public aquariums have played in valuable research that can have a direct impact on the trade. For example, through the well-known Rising Tide Initiative and similar programs rearing fishes from eggs collected at public aquariums, public aquariums are playing an active role in closing the life cycle on the captive culture of more species of marine fishes. Increasing the number of captive-bred fishes available to home aquarists—especially beginning aquarists—is a critical effort when it comes to sustainability. This is, however, a double-edged sword, as too often captive-bred animals are held up as the gold standard of a sustainable aquarium trade. The much more complex story—and one public aquariums are well positioned to tell—is that continuing to support sustainable wild fisheries in addition to increasing captive breeding can provide invaluable economic incentive to conserve aquatic ecosystems.

Is it a mandate for public aquariums to reform an aquarium trade that is viewed by many as a threat to aquatic conservation? Of course not, but as the Zoo Biology paper makes clear, public aquariums do have an opportunity here, and engaging in that opportunity does make good sense from an economic and environmental standpoint. While it may not be public aquariums’ responsibility to reform the trade, it should be acknowledged that their failure to act would perpetuate the status quo and potentially even allow the situation to become worse. Conversely, an approach similar to that which aquariums took with seafood a decade ago has the power to effect real change and empower a consumer-driven conservation initiative that will benefit species, habitat, and people.

Sea Change

Kelp Forest exhibit at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Image: Sky Collins/Shutterstock.

As my colleague remarked last night, “The same approaches from the same people haven’t worked in 20 years.” What has worked, however, are anti-trade activists’ campaigns to end the marine aquarium trade (consider the mounting efforts to ban livestock collection in Hawaii). Isn’t it time aquarists stopped adopting the victim mentality in the face of these threats to the aquarium hobby? Isn’t it time aquarists supported real and substantive reform?

Before criticizing those who are criticizing the trade, aquarists would be wise to do some introspection and decide on which side of history they want the trade to fall. Will the aquarium trade and hobby be viewed as a force for good? Will aquarists be seen as standing in the trenches on the front line of ocean conservation? Or will the aquarium trade be seen as little more than wildlife trafficking with a “get it while you can” mentality?

As someone who has covered sustainability issues in the aquarium trade for several years now, I believe the necessary trade reform is going to be driven by some new players—entities that have the incentive, resources, and imagination to achieve what others have been unable or unwilling to achieve. As discussed above, public aquariums and, by extension, the American Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) and the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) will play a leading role in positive reform, but so will others.

Home aquarists and many in the trade have not traditionally embraced many of these “new” players. In fact, some would be hard pressed to even identify them as players, but their efforts and engagement in the issues that will make or break the aquarium trade have already proven they are the ones with the incentive, the resources, and the will to make a change. Expect, along with public aquariums, to see the Petcos and Disneys and Sea Worlds of the world define the agenda in the coming months. Expect the Pet Industry Joint Advisory Council (PIJAC) to engage on behalf of, and in conjunction with, these entities. Aquarists and individuals involved with the trade have a choice here—will the likes of public aquariums, Petco, Disney, and Sea World be embraced or shunned? Will aquarists become fractured and segmented over petty arguments about who really knows best and what the best path forward ought to be, or will aquarists support these emerging thought leaders and enter into a constructive dialogue with them? Will those in the trade expand their relationships with these players and actively collaborate to increase the sustainability of the trade, or will they insist on a business-as-usual approach that will only push the trade closer to the abyss?

The marine aquarium hobby and livestock trade is at a crossroads. It finds itself at the intersection of outdated models and new approaches, resistance to change and openness to new possibilities. Society is becoming “greener,” and while some of that is no doubt little more than greenwashing, there are real steps being taken toward a more sustainable future.

A growing number of consumers are not only familiar with sustainability—they are now demanding it. Corporate responsibility initiatives, often born of enlightened self-interest, are on the rise. The aquarium trade can and should be part of this. What if, for example, we could hold the aquarium livestock trade accountable by walking into the local fish store and knowing which fishes were collected with cyanide in the same way DNA testing can insure accountability for the seafood industry?

The aquarium industry is going to change; the only question that remains is who will be responsible for that change. Will it be a change from within, driven by those of us who understand the trade, or will it come from anti-trade activists and Draconian measures levied by those who know little about the real impacts and educational rewards of keeping an aquarium? It’s not difficult to imagine that we are on the brink of an important sea change, and I, for one, embrace this new direction.

References

Tlusty, M.F., A.L. Rhyne, L. Kaufman, M. Hutchins, G.M. Reid, C, Andrews, P. Boyle, J. Hemdal, F. McGilvray, and S. Dowd. 2013. Opportunities for public aquariums to increase the sustainability of the aquatic animal trade. Zoo Biol 32 (1): 1–12. doi: 10.1002/zoo.21019. Epub 2012 May 1.